The New Star of Japanese Yakiniku

Among all the cuts of Japanese BBQ, one name keeps rising to the top – Harami. It’s not the classic short rib (Kalbi), nor the premium loin. Yet more and more people say, “I just want to eat Harami tonight.” The reason is simple: it perfectly balances rich flavor and light texture.

Neither Red Meat nor Offal – A Fascinating Hybrid

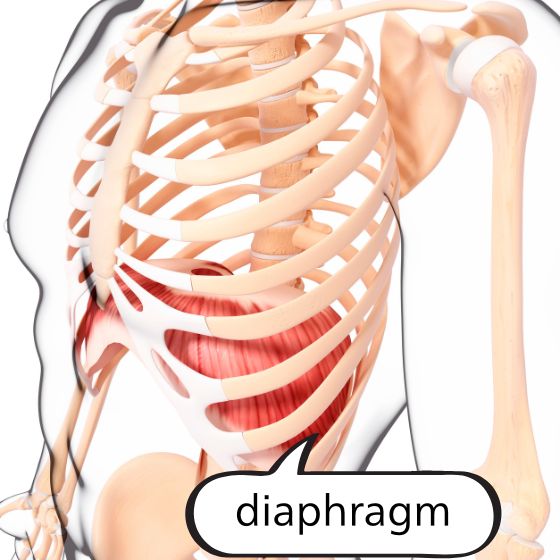

Technically, Harami belongs to the offal category, since it comes from the diaphragm – the muscle used for breathing. But its appearance and texture resemble lean meat rather than organ meat. This in-between nature gives Harami its mysterious charm.

Once You Taste It, You Understand

It’s tender, juicy, and full of beefy aroma – yet never heavy. It delivers the satisfaction of a short rib with the lightness of lean beef. That is why it has captured the hearts of both health-minded diners and true meat lovers alike.

The Hidden Truth Behind Its Popularity

Today, many people say: “Kalbi feels too fatty, but lean meat is too plain.” Harami fills that gap perfectly. However, few restaurants can serve truly exceptional Harami. The reason? High-quality Wagyu Harami is incredibly difficult to source.

Why Wagyu Harami Is So Rare

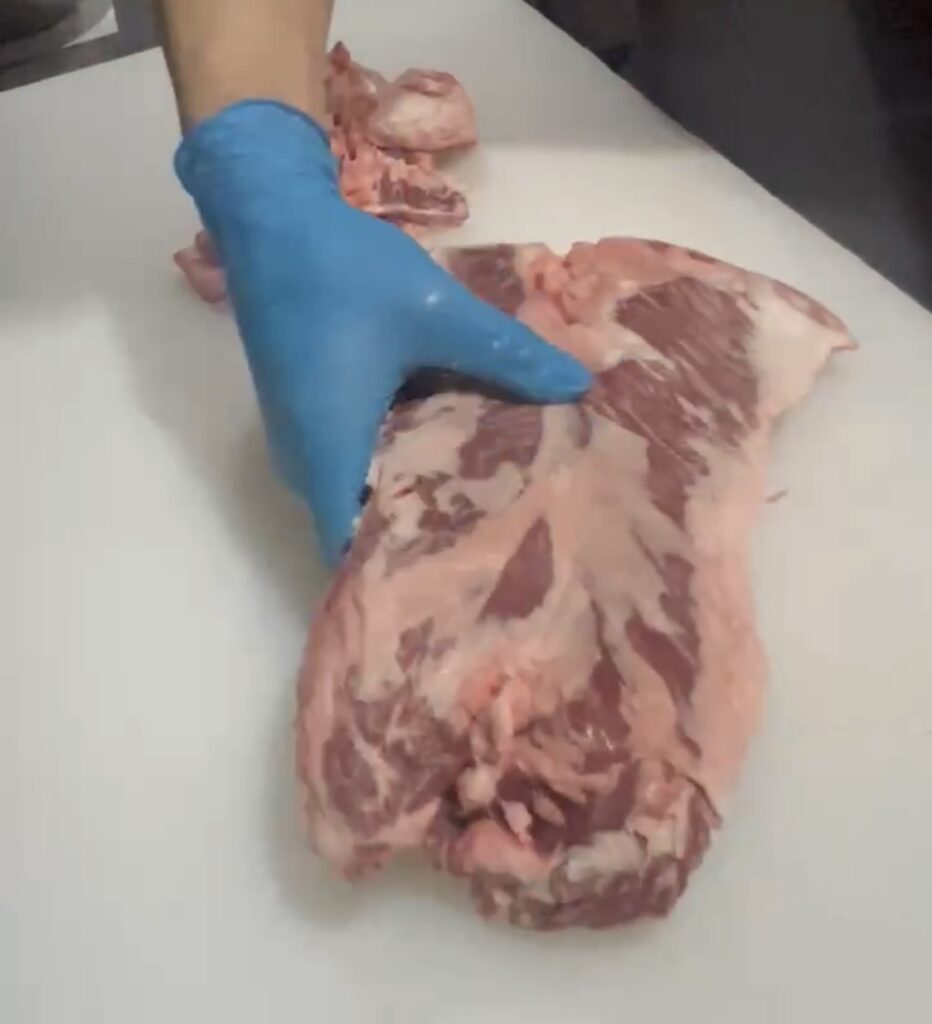

From a whole cow, only about 4–5 kilograms (8–11 pounds) of Harami can be harvested. But even then, much of it contains thick membranes and sinew, making only half of that suitable for yakiniku. In other words, each animal yields barely 2 kilograms (4–5 pounds) of usable meat.

Low Yield, High Skill

This cut is known for its poor yield. Fat marbling and muscle fiber vary dramatically from cow to cow, so achieving consistent quality requires expert trimming and years of experience. Handling Harami properly is truly a craftsman’s job.

Why Small Artisan Shops Shine

Only restaurants with long-standing partnerships with trusted butchers can obtain high-quality Wagyu Harami regularly. That relationship of trust and skill has become one of the most valuable assets in the modern yakiniku industry.

That’s precisely why only a limited number of restaurants can reliably source Wagyu harami.

Only through long-standing trust with meat wholesalers can high-quality harami be obtained.

This combination of discerning expertise and strong bonds has become the most valuable asset in today’s yakiniku industry.

For butchers, harami is a cut that yields almost no profit.

A single skirt steak weighs very little, so even selling it at a high price yields only a small profit. On the other hand, what truly generates profit for butchers isn’t skirt steak, but “yakiniku restaurants that buy large quantities of carcasses (cut meat like loin and round cuts).”

Therefore, butchers allocate Wagyu skirt steak as a privilege to restaurants that consistently support them by purchasing significant amounts of carcasses. This is the fundamental reality of the Wagyu skirt steak procurement world.

Beyond a Trend – Harami as a Culinary Culture

Harami may be the face of today’s yakiniku boom, but its rise isn’t just a passing trend. It’s a story of craftsmanship, supply networks, and devotion to the art of meat. Soft yet flavorful, aromatic yet refined – Harami is the product of both nature and human skill, a miracle balance that represents the heart of Japanese BBQ culture.

In the next chapter, we’ll explore where exactly the Harami is located, why it’s sometimes called “Skirt Steak,” and how its anatomy makes it so unique among all cuts of beef.

Where Exactly Is Harami Located?

The Diaphragm – The Muscle of Life

Harami comes from the diaphragm, the thin sheet of muscle that separates a cow’s lungs and liver. It moves up and down with every breath, helping the animal inhale and exhale. In humans, it corresponds to the area that twitches when you hiccup – that’s right, Harami is literally the “breathing muscle.”

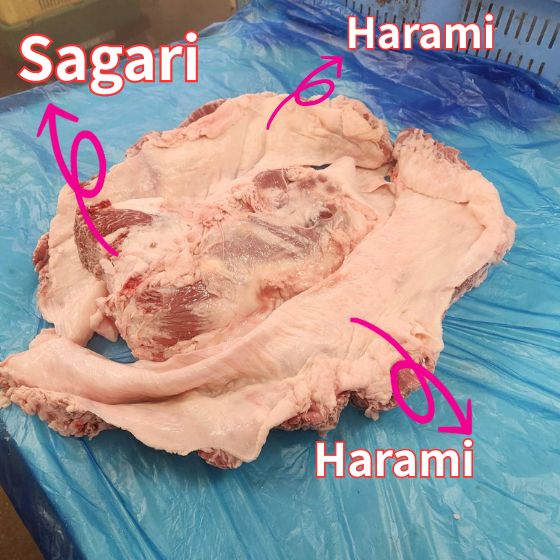

The Relationship Between Harami and Sagari

The diaphragm has two main sections: Harami and Sagari. Harami lies along the inner side of the ribs, while Sagari sits deeper inside, between the ribs and kidneys. Because of this difference in position, their muscle fibers run in different directions. Harami tends to be juicier and more marbled with fat, while Sagari is leaner and has a firmer bite. Both are part of the same muscle group, yet their flavors and textures are surprisingly distinct.

Why It’s Classified as Offal but Feels Like Lean Beef

Technically, Harami is considered offal (organ meat) because it’s attached to internal organs rather than bone. However, it doesn’t have the chewy texture or strong aroma typical of organ meats. Its fine muscle fibers and deep beefy flavor make it feel more like lean steak than offal – a rare hybrid of both worlds.

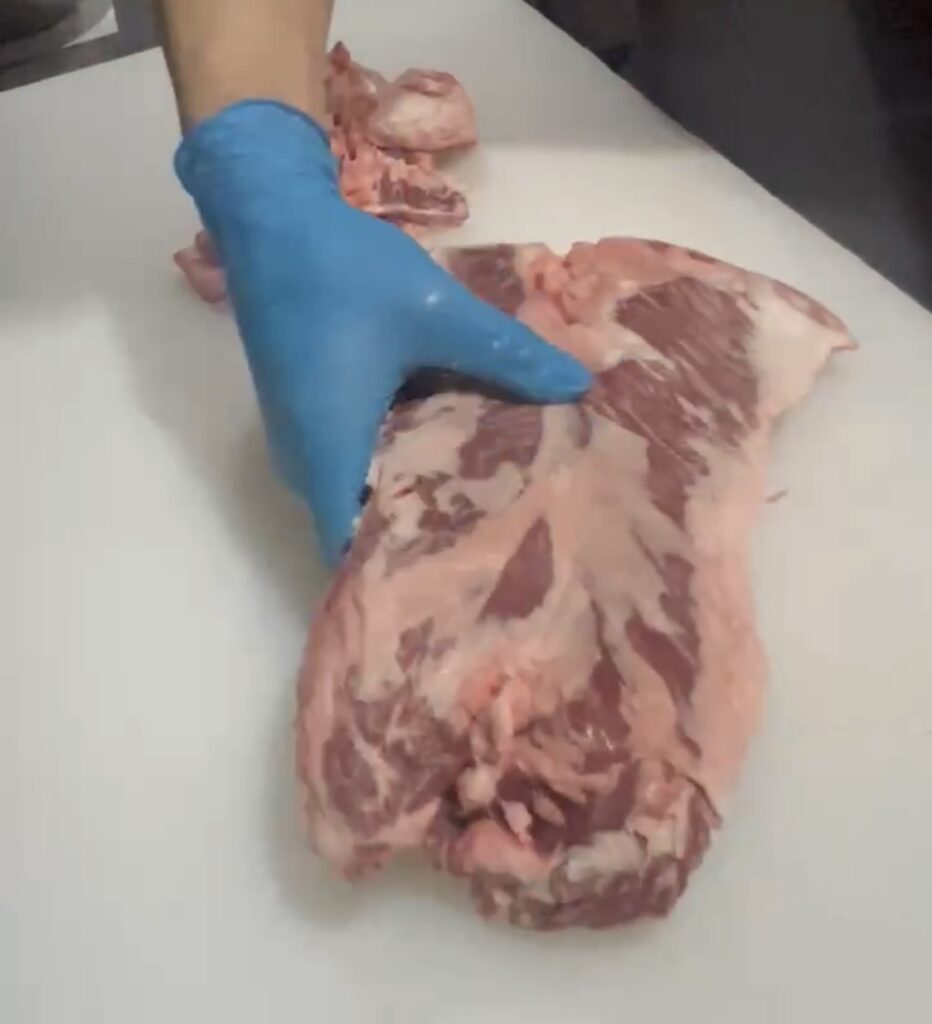

The Unique Structure of Wagyu Harami

One of the most fascinating features of Wagyu Harami is its structure. It’s not sinewy, but rather covered in a thick layer of fat. Imagine a piece of lean meat wrapped entirely in soft fat – that’s how Harami looks inside a Wagyu carcass. The thickness of this fat varies greatly depending on the part, making trimming extremely delicate work.

Remove too much fat and you lose its flavor. Leave too much, and the richness overwhelms the meat when grilled. In other words, the perfect balance between fat and lean defines a great Harami. This is why it’s often called “a cut that’s completed by the chef’s knife.”

How Imported Harami Differs

Imported Harami from the U.S. or Australia is usually trimmed at the processing plant before being shipped to Japan. Most of the outer fat and membranes are removed for efficiency and uniformity. As a result, it looks cleaner and is easier to handle, but it lacks the rich aroma and depth of Wagyu. If imported Harami is “refined red meat,” then Wagyu Harami is “red meat wrapped in flavor.”

The Craftsmanship Behind Every Slice

A single cow yields about 4–5 kilograms (9–11 pounds) of diaphragm meat, but less than half of that can be served as yakiniku. Thick layers of fat must be carefully removed by hand, and every cut demands precision. That’s why Wagyu Harami is often called a “craftsman’s cut” – it’s finished not by a machine, but by skilled hands.

Neither Red Meat nor Offal – The Middle Ground of Flavor

Harami exists in the middle ground between red meat and offal. It’s a muscle that keeps the animal alive, yet when grilled, it becomes aromatic, tender, and deeply flavorful. Each slice carries the rhythm of life and the mark of human craftsmanship – the true essence of Japanese yakiniku.

In the next chapter, we’ll look deeper into the Sagari, the other half of the diaphragm, and discover how its flavor and texture differ from Harami.

Which Muscle Does Harami Correspond to in Humans?

The Muscle That Moves When You Hiccup

Harami comes from the cow’s diaphragm – the muscle that makes breathing possible. In humans, it corresponds to the area that twitches when you hiccup. This thin sheet of muscle stretches between the chest and abdomen, moving downward when you inhale and upward when you exhale. It’s what allows the lungs to expand and contract. In other words, if the diaphragm stops, breathing stops – it is quite literally the muscle of life.

A Muscle That Never Rests

The diaphragm works around the clock. Even while you sleep, it contracts and relaxes tens of thousands of times each day. Because of this constant motion, its fibers are fine, soft, and built for endurance. It’s classified as a “slow-twitch” or red muscle, rich in myoglobin – the same protein that gives red meat its deep color.

Why It Feels Like Lean Meat

This structure explains why Harami looks and feels so much like lean steak. A constantly moving muscle develops fine fibers and holds plenty of oxygen, which helps it stay tender even after grilling. That’s why each bite of Harami releases deep, lingering flavor instead of becoming tough or dry.

The Taste of Life Itself

Harami is one of the most vital and expressive muscles in a cow’s body – a true “breathing muscle” that quietly sustains life. In humans, it would be the calm rhythm inside your chest, the silent motion that keeps you alive. To grill and savor it is, in a way, to taste the rhythm of life itself.

In the next chapter, we’ll look at Sagari – the other part of the diaphragm – and explore how its flavor and texture contrast beautifully with Harami.

The The Difference Between Harami and Sagari

Two Distinct Characters Within the Diaphragm

On any yakiniku menu, you’ll often find Harami and Sagari. They may look similar, but they are completely different cuts. Both come from the cow’s diaphragm – the breathing muscle – yet their positions, flavors, and textures differ entirely. Understanding the difference between them adds a new layer of depth to your yakiniku experience.

Harami – The Golden Balance of Lean and Fat

Harami is located on the rib side of the diaphragm. Although technically considered offal, it looks and tastes just like lean beef. Its fine muscle fibers hold a modest amount of fat, creating a perfect harmony between red meat and richness.

As it grills, the fat melts and releases a sweet aroma, while the lean meat offers depth and juiciness. This “lightly rich” quality is what makes Harami one of the most beloved cuts in yakiniku. It’s less fatty than short rib yet richer than loin – the golden middle ground of flavor and texture.

Even within a single piece, Harami shows subtle variations: the edges carry more marbling, while the center is leaner and cleaner. Grilling it quickly over high heat enhances aroma, while slow cooking over gentle heat brings out natural sweetness. Each bite reveals a different shade of flavor.

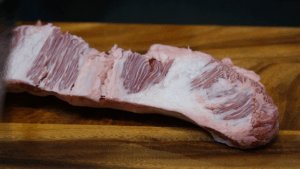

Sagari – The Hidden Star on the Back Side

Sagari comes from the back side of the diaphragm, closer to the spine. It contains less fat overall and has a smooth, refined texture – slightly leaner than Harami. However, calling Sagari simply “healthy red meat” would miss its true charm.

At one end of Sagari lies the “kobu,” a small lump of intensely juicy meat. Thin layers of fat run through its fibers, creating deep, concentrated umami. Because this part yields only a few slices per cow, it’s known among chefs as an ultra-rare delicacy. Some professionals even say the kobu is tastier than the thick center of Harami.

And between the two main parts of Sagari lies a thick inner sinew called the “Oni-suji”. This legendary muscle fiber is said to be the most flavorful sinew in the entire cow. Though it looks tough, when trimmed and cooked properly it transforms into a bite bursting with rich, dense flavor – a true “king of sinews.” Only a few small pieces can be harvested from each animal, making it one of the rarest and most prized finds in the yakiniku world.

Overall, Sagari feels light and clean, yet each chew releases an elegant, lingering umami. It’s a cut that expresses the pure essence of beef without relying on fat.

Harami and Sagari – Two Opposite Souls of the Same Muscle

Though they come from the same diaphragm, Harami represents balance – the harmony of lean and fat – while Sagari embodies refinement – the quiet depth of red meat, the richness of the kobu, and the intensity of the Oni-suji. Neither is superior; they simply reveal different sides of the same muscle. The way you season and grill them brings out completely different personalities.

Within this single sheet of diaphragm lies contrast: fat and lean, tenderness and strength, calm and intensity. How it’s grilled, and how it’s enjoyed, reflects both the philosophy of the craftsman and the sensitivity of the diner.

How to Grill Harami and Sagari

Grilling Defines the Taste

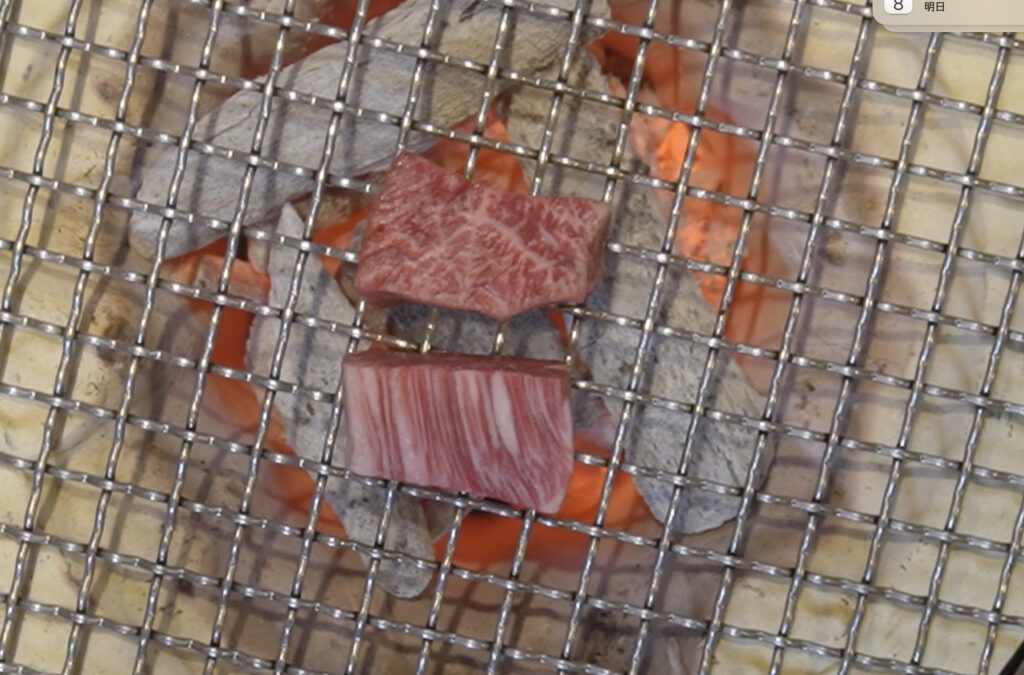

In yakiniku, how you grill changes everything. Harami and Sagari come from the same diaphragm muscle, yet their ideal grilling methods differ completely. Understanding how heat interacts with each cut is the key to unlocking their true flavor.

Charcoal, Wire Mesh, and Strong Heat from a Distance

The best way to grill both cuts is with charcoal on a wire mesh over high but distant heat – the classic “strong heat from a distance.” The key is to flip the meat frequently as it cooks. This prevents overcooking on one side and helps render fat evenly for a crisp surface and juicy center.

Instead of burning the meat with direct flames, use the gentle infrared heat of the charcoal to warm the inside gradually. It’s all about balance – not too close, not too far. This setup allows the fat to melt slowly, enhancing the meat’s aroma without drying it out.

Harami: Stays Tender Even When Fully Cooked

Harami contains a moderate amount of fat, which protects it from becoming tough even when cooked thoroughly. As the fat melts, it coats the muscle fibers, keeping the texture soft and juicy. You can grill Harami a bit longer without fear – it remains tender and flavorful.

For the perfect Harami, grill until the surface is nicely browned but the center still has a faint blush of pink. Finish it with a quick rest to let the juices settle. A light touch of tare sauce at the end, seared slightly by the charcoal heat, brings out a deep, smoky sweetness. Aim for a medium doneness – it’s the sweet spot for Harami.

Sagari: Best Enjoyed Rare

Sagari has less fat and loses moisture more easily, so overcooking will make it dry and firm. The goal is to keep it rare to medium-rare. Flip it often over the charcoal to seal in juices while browning the surface. Each turn keeps the moisture inside, resulting in a crisp edge and tender interior.

The trick is the same even without charcoal – when using a pan or electric grill, flip the meat every few seconds. Quick, frequent turns cook the meat evenly and preserve juiciness far better than leaving it on one side too long.

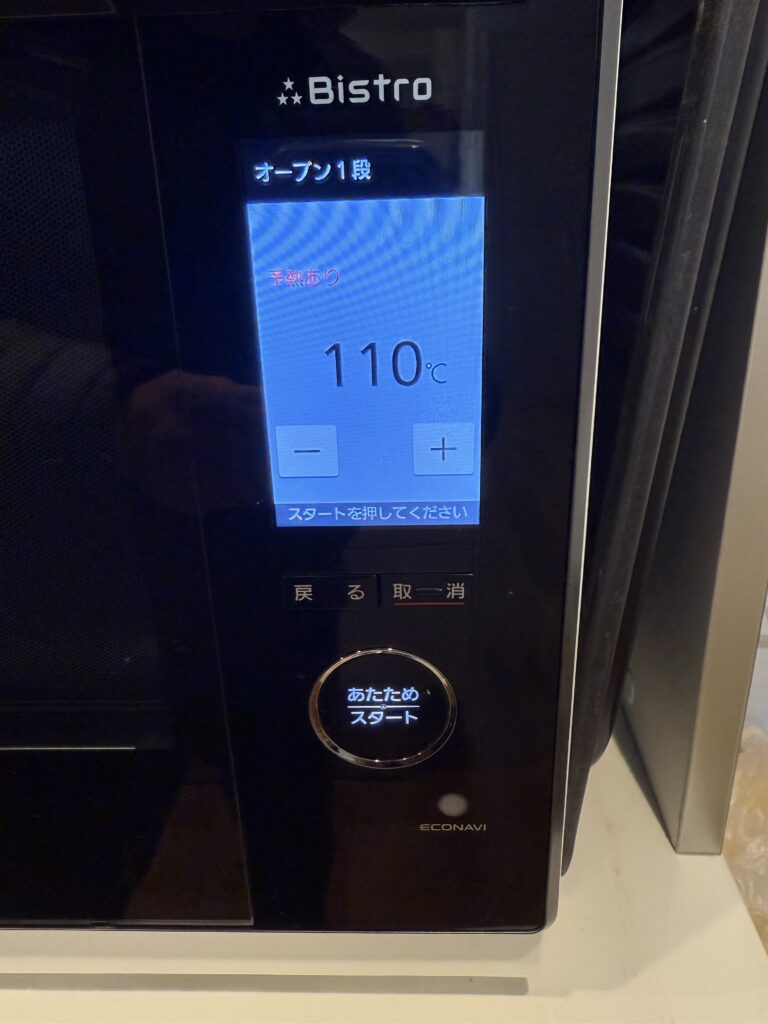

Steak-Style Sagari: Oven and Pan Technique

If you’re cooking a whole piece of Sagari like a steak, start by warming it in a 110°C (230°F) oven for about 15 minutes. This allows the heat to reach the center gently without losing moisture. Then, transfer it to a hot pan and sear all sides over high heat to create a crisp, caramelized crust.

The result is a beautiful rare steak – tender inside, aromatic outside. The two-step method of low-temperature heating + quick sear works especially well for Sagari, enhancing its natural texture and depth of flavor.

Grilling Is a Conversation Between Fire and Meat

Harami expresses its flavor through aroma and fat, while Sagari reveals its purity through temperature control. Their approaches are different, yet both demand the same principle – watch the meat and listen to it.

The sound of sizzling fat, the color change, the rising aroma – the meat speaks. A true craftsman knows exactly when to stop the fire and let the flavor rest. Grilling is not just technique; it’s a dialogue with the ingredient – a form of respect for the meat itself.

Is There “Harami” in Other Animals?

When you hear “Harami,” you probably think of beef. But pigs, chickens, and even fish each have their own cuts known as “Harami.” While the position and function of these muscles differ across species, they all share one thing in common – they are core muscles that sustain life and movement.

Beef Harami (Diaphragm)

In cattle, Harami refers to the diaphragm – the muscle that separates the chest cavity from the abdomen and drives breathing. Because it moves constantly, its fibers are fine and densely packed with flavor. Though technically classified as offal, its texture resembles lean meat with a rich, balanced taste of fat and umami.

Only about 4–5 kilograms can be obtained from a single cow, making it a rare and highly prized cut. It embodies the essence of a “muscle that’s always in motion.”

Pork Harami (Diaphragm)

Pigs also have a diaphragm, known as pork Harami or pork Sagari. It’s smaller and firmer than beef Harami but has a deep, savory aroma when grilled. As in cattle, this muscle aids breathing – a true life-supporting muscle – and its constant motion gives it a concentrated flavor full of amino acids and umami.

Chicken Harami (Abdominal Muscle)

Chicken Harami, however, comes from a completely different part of the body. Unlike mammals, chickens do not have a diaphragm. Instead, their so-called “Harami” refers to a small section of the abdominal wall muscle – the muscle that supports the lower body and protects the internal organs.

It’s located near the base of the thighs, forming part of the abdominal wall. From one chicken, only about 4 to 10 grams can be taken, making it an extremely rare cut. According to Japan’s official meat classification, it’s categorized as offal (horumon) rather than standard meat.

Though tiny, chicken Harami has a springy texture and a surprisingly rich flavor. It doesn’t function as a breathing muscle like beef Harami, but it plays an important role in supporting the bird’s core and protecting its organs. This proximity to the internal cavity – and its role as a structural, protective muscle – gives it the same naming sense as Harami, despite being anatomically different.

Fish Harami / Harasu (Belly Meat)

Fish also lack a diaphragm, but their belly muscles correspond to what we call “Harami.” These include the well-known Harasu and Harami cuts – the fatty meat along the belly and ribs, often seen in salmon, tuna, or other migratory fish.

These muscles are heavily used during swimming and thus accumulate fat and flavor. They’re prized for their melt-in-your-mouth texture and rich aroma when grilled.

- Harasu: The fattiest part of the belly, famous in salmon and trout – tender and buttery when cooked.

- Harami: The portion closer to the bones, slightly firmer with balanced fat and umami.

In fish, these belly muscles serve as the motor of motion, much like how the diaphragm fuels movement in mammals. They too represent “the muscle that keeps life moving.”

Muscles That Keep Life Moving Are the Tastiest

Beef Harami supports breathing. Pork Harami does too. Chicken Harami supports posture and organ protection. Fish Harami powers swimming. Different roles – but the same truth: these are muscles that never rest.

Such muscles have abundant blood flow and are rich in amino acids and myoglobin, producing deep aroma and flavor. In short, the muscles that sustain life are the ones that taste the best.

Conclusion

The word “Harami” represents more than just a cut of meat. It symbolizes the muscles that drive life itself. Whether in cattle, pigs, chickens, or fish, these constantly moving muscles take different forms and flavors, but all embody the same principle – life, structure, and taste in motion.

What Harami Teaches Us About Life and Craft

Among all the cuts in Japanese yakiniku, few captivate people like Harami. It looks like lean meat but isn’t. It’s classified as offal, yet feels refined. Existing somewhere between red meat and organ, Harami has earned a special place in Japan’s dining culture – a cut that bridges contradiction and harmony.

The Beauty of Contradiction in a Single Muscle

Harami is the diaphragm – the muscle that drives breathing. Breathing is life itself, a rhythm that never stops. That’s why Harami can be called the meat that holds the pulse of life.

It’s a muscle, yet an organ. Rich with fat, yet never heavy. Intense in flavor, yet clean in aftertaste. It’s as if all contradictions of meat coexist in perfect balance within this one cut. That complexity is what makes Harami so irresistibly human – nuanced, imperfect, and full of depth.

Flavor Born from Trust and Craftsmanship

High-quality Wagyu Harami is extremely rare. Only about 4–5 kilograms can be taken from an entire cow, and even less meets the standards of fine yakiniku. It can’t simply be purchased – it must be earned through relationships built over time.

Butchers, chefs, and grill masters – each plays a role. Their connection is not just about skill, but trust. Behind every delicious Harami lies a network of people who share the same dedication to quality.

The Art of Fire and Timing

When Harami meets fire, fat sizzles, aroma rises, and flavor blooms. In those brief seconds, instinct and experience merge. Too much heat, and it becomes tough; too little, and it stays heavy. Perfect grilling requires a conversation – a dialogue between fire and meat.

In that sense, yakiniku is less about cooking and more about listening. It’s a living art where mastery lies in knowing when to stop, when to turn, when to let the flavor speak for itself.

Harami as a Symbol of Japanese Yakiniku Culture

Harami’s importance goes far beyond taste. After World War II, it became the people’s meat – affordable, satisfying, and communal. As Japan’s Wagyu culture evolved, Harami transformed from a humble cut to a symbol of rarity and refinement.

Once considered part of the “outer rib,” it was redefined through the eyes and hands of craftsmen. The word “Harami” itself came to represent Japan’s unique approach to food – where technique, respect, and curiosity give birth to new value. It’s not just meat; it’s a piece of history cooked over charcoal.

Tasting Life Itself

Every bite of Harami carries the memory of breath – a muscle that once moved with life. The same holds true for pork, chicken, and fish: the most flavorful muscles are always the ones that moved the most. In other words, the taste of life is found in motion.

To eat such meat is to honor that motion, that life. Harami reminds us that “to eat” is not simply to consume – it is to appreciate the life that sustained us.

Conclusion

Harami is more than a part of yakiniku. It’s where craft, trust, culture, and life intersect. Fire speaks to meat, and craftsmen listen with care. In that fleeting dialogue, flavor becomes art.

To eat Harami is not just to taste meat – it’s to taste Japanese culture and the quiet heartbeat of life itself.

Wagyu Yakiniku Kuro5

IKEBUKURO Main Restrant

1F Shima 100 building ,2-46-3, Ikebukuro, Toshima-ku , Tokyo 171-0014

https://en.kuro5.net/restaurant/honten

Wagyu Yakiniku Kuro5

IKEBUKURO East Exit Restrant

2F Need Building, 1-42-16 Higashi-Ikebukuro, Toshima-ku, Tokyo 170-0013

https://en.kuro5.net/restaurant/higashiguchi

Wagyu Yakiniku KURO5

Kabukicho

1F Sankei Building, 2-21-4 Kabukicho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo

https://en.kuro5.net/restaurant/kabukicho

Official Instagram: @kuro5yakiniku